Version control systems are tools used to track changes to files and folders under their purview. A VCS will maintain a history of changes, and facilitate collaboration by tracking metadata like who created each snapshot of changes and why.

Version control is useful because it lets you examine old snapshots of a project, keep a log of why certain changes were made and when, and work on parallel branches of development. It also helps to clarify what other people have changed, as well as providing a means to resolve conflicts in concurrent development.

There are a number of unique VCSs, but Git has emerged as the de facto standard.

The Git Data Model

From the Git Book:

“Git is fundamentally a content-addressable filesystem with a VCS user interface written on top of it.”

Yikes!

Git’s interface is a leaky abstraction, and learning a handful of commands to use like magic incantations can lead to confusion really quickly. Indeed, Git has a reputation in the industry, captured by this XKCD comic.

It’s true that Git’s interface is a bit ugly, especially to a new user that may not be accustomed to CLI tools. But the underlying design and principles of Git are beautiful. An ugly interface has to be memorized, but a beautiful design can be understood.

Snapshots

Git models the history of a collection of files and folders as a series of snapshots. In Git parlance, a file is called a blob.

Try this out!

You can have Git tell you the object type of any object in Git, given its SHA-1 key.

git cat-file -t [SHA-1 key]

Directories are called trees, and they map names to blobs or trees, since a directory can house both files and directories.

A snapshot is the state of the top-level tree that is being version controlled. An example tree might look like:

<root> (tree)

|

+- dir (tree)

| |

| +- file1.txt (blob, contents := 'Hello, World!')

|

+- file2.txt (blob, contents := 'Git is neat!')

Modeling a History: Relating Snapshots

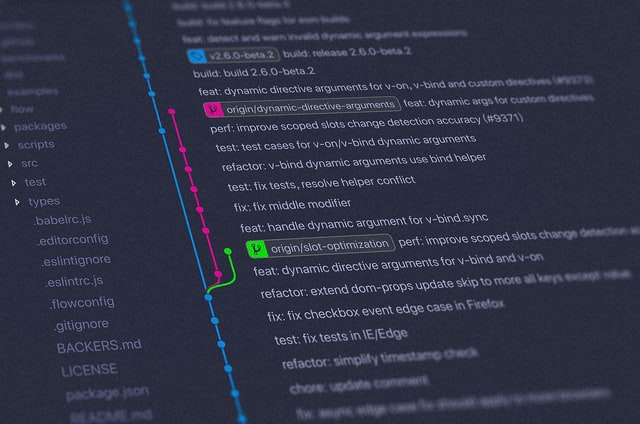

Rather than implement a linear history of snapshots, Git uses a DAG. Each snapshot in Git refers to a set of ‘parents’, the snapshots that preceded it. A set of parents is used instead of a single parent (as it would be in a linear history) because a snapshot may descend from multiple parents, as would be the case when merging branches of parallel development.

Git calls these snapshots commits. Visualizing a commit history could look something like this:

o <-- o <-- o <-- o

^

\

--- o <-- o

Each o corresponds to individual commits in the history.

The arrows point back to parent commits (Git uses a comes before relation, not a comes after relation).

Note that after the third commit, there are two independent branches of history progressing in parallel.

In a future commit, these branches could be merged into a commit that incorporates both histories.

That would look something like this:

o <-- o <-- o <-- o <---- o

^ /

\ v

--- o <-- o

Git Commits are Immutable

Commits, as well as objects in general, are immutable in Git. A history of commits can still be edited, but those edits take the form of new commits that replace the old ones.

This is a topic of some contention, on which I am still undecided. You can effectively “rewrite history” with certain git commands.

The Git Model in Pseudocode

Let’s lay out the Git model, as we’ve discussed it so far, as pseudocode.

// a blob (file) is a bunch of bytes

type blob := array<byte>

// a tree (directory) contains named trees and blobs

type tree := map<string ~> tree | blob>

// a commit has parents, metadata, and the toplevel tree

type commit := struct {

parents: array<commit>

author: string

message: string

snapshot: tree

}

Laid out like this, the Git model is a simple and straightforward VCS. We’ll refer back to this as we expand our understanding of Git in the next sections.

Objects and Content Addressing

An Object can be a blob, a tree, or a commit.

type object := blob | tree | commit

In a Git data store, objects are content-addressed by their SHA-1 hash.

objects := map<string ~> object>

fn store(object):

id = SHA1(object)

objects[id] = object

fn load(id):

return objects[id]

So blobs, trees, and commits are all objects. When they reference other objects, they don’t need to contain the referenced object itself. Rather, they can use the data store to refer to another object by it’s SHA-1 hash.

References

All of our snapshots can be identified by their SHA-1 hashes. That’s convenient if you are a computer capable of calculating and remembering 40-character strings of hexadecimal digits. Not so much if you’re a mere mortal.

Git uses a system of human-readable names for hashes, called references.

References are pointers to commits.

Unlike objects (which we know are immutable), references can be updated to point to a new commit.

For example, the main (or master in legacy repositories) reference usually points to the latest commit in the main branch of development.

Updating our pseudocode to include this reference functionality:

// a reference maps a name ~> id (hash)

references = map<string ~> string>

fn update_reference(name, id):

references[name] = id

fn read_reference(name):

return references[name]

fn load_reference(name | id):

if name in references:

return load(references[name])

else:

return load(id)

This notion of mutable references allows us to have an additional picture of where we currently are in the tracked history. This “where we currently are” reference is a special reference called HEAD.

Repositories

The final piece of the data model puzzle! A repository is the collection of data store objects and references. Seems like a bit of an anti-climax, but that’s the whole point of the Git data model. The beauty is in the simplicity of the abstraction.

On disk, Git just stores objects and references.

Command line git commands are means to manipulate the DAG of commits by doing things like adding objects and adding or updating references.

The whole point of understanding Git’s data model is to understand, when typing any git command, how Git is changing the underlying graph data structure.

Conversely, if you’re trying to accomplish a specific task, there’s probably a git command to achieve it.